Steeltoe Stream Reference

This section explores the components that make up the Steeltoe Stream framework together with how to build Stream-based applications.

Main Concepts

Steeltoe Stream provides a number of abstractions and opinions that simplify the writing of message-driven microservice based applications. This section gives an overview of the following:

- Application Model

- Binder Abstraction

- Binding Abstraction

- Persistent Publish-Subscribe

- Consumer Types

- Consumer Groups

- Durability

- Partitioning

- Binder SPI

Application Model

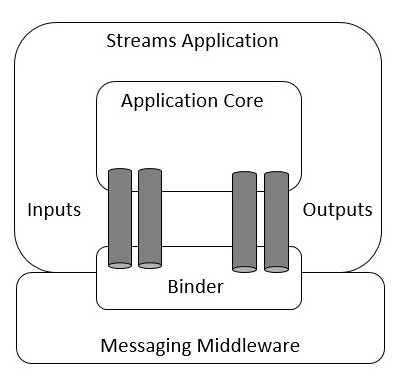

A Stream application is composed of middleware-neutral core microservices enhanced by Steeltoe Stream. Application developers typically do not have to deal with the underlying messaging middleware and instead can focus on the microservice logic itself. Normally the service communicates with the outside world through input and output channel abstractions injected into it by the Steeltoe Stream infrastructure. Channels are a programming abstraction that represent messaging destinations. Services can send and receive messages to and from destinations using these channels . Steeltoe Stream automatically configures channels for you and connects them to external messaging systems through middleware-specific binder implementations. Binders are components provided by Steeltoe or other third parties package providers.

Binder Abstraction

Steeltoe uses a binder abstraction to make it possible for Stream-based services to be flexible in how they connect to messaging middleware. Steeltoe automatically detects and uses whatever binder it finds in the services startup directory when attempting to connect to the messaging system. This enables developers to use different types of messaging middleware without the need to change the applications code; You simply include a different binder at deployment time.

For more complex use cases, you can package multiple binders with your services and configure it to choose the correct binder for the different channels or destinations used by the service at runtime.

The configuration can be provided through normal .NET configuration providers, including command-line arguments, environment variables, and/or appsettings.json.

For example, setting the configuration key spring:cloud:stream:bindings:input:destination to raw-sensor-data can be used to configure the channel named input to be bound to the raw-sensor-data RabbitMQ exchange when using a RabbitMQ binder.

Currently, Steeltoe provides a single binder implementation for Rabbit MQ. Future binders provided by Steeltoe are on the roadmap including Kafka and others. You can also use the extensible Binder SPI to write your own should you need to.

Binding Abstraction

Steeltoe also uses a binding abstraction to provide a way to define the name and types of destinations available to the Stream-based microservice. Bindings provide a bridge between the destinations in the external messaging system and the methods in the application which act as message producers and/or consumers.

Persistent Publish-Subscribe

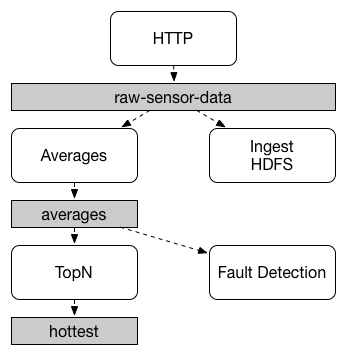

Communication between microservices follow a publish-subscribe model where data is broadcast through shared topics. This can be seen in the following figure, which shows a typical deployment for a set of interacting Stream microservices.

Data reported by sensors to an HTTP endpoint is sent to a common destination named raw-sensor-data.

Receiving data from the destination, the data is independently processed by a microservice based application that computes time-windowed averages and by another microservice that ingests the raw data into HDFS (Hadoop Distributed File System).

In order to process the data, both microservices declare the topic as their input at runtime.

The publish-subscribe communication model reduces the complexity of both the producer and the consumer and lets new services be be easily added to the topology without disruption of the existing flow. For example, downstream from the average-calculating microservice, you can add an additional service that calculates the highest temperature values for display and monitoring. Additionally, you can then add another service that interprets the same flow of averages for fault detection. Doing all communication through shared topics rather than point-to-point queues reduces coupling between microservices.

While the concept of publish-subscribe messaging is not new, Stream takes the extra step of making it an opinionated choice for its application model. By using native middleware support, Stream also simplifies use of the publish-subscribe model across different platforms.

Consumer Types

Two types of consumer are supported by the Stream infrastructure:

- Message-driven (sometimes referred to as Asynchronous)

- Polled (sometimes referred to as Synchronous)

The default is to implement message driven consumers, but when you wish to control the rate at which messages are processed, you might want to use a synchronous consumer.

Consumer Groups

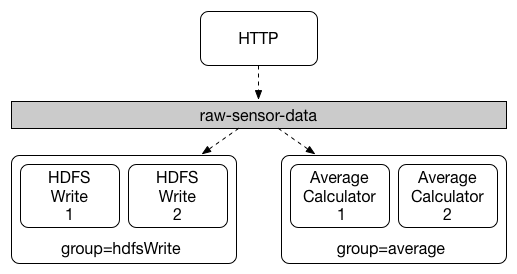

While the publish-subscribe model makes it easy to connect microservices through shared topics, the ability to scale up by creating multiple instances of a given service is equally important. When doing so, different instances of a microservice are placed in a competing consumer relationship, where only one of the instances is expected to handle a given message.

Steeltoe Stream models this behavior through the concept of a consumer group. Stream consumer groups are similar to and inspired by Kafka consumer groups.

Each consumer binding can configure the spring:cloud:stream:bindings:<channelName>:group key to specify a group name.

For the consumers shown in the following figure, this key would be set to spring:cloud:stream:bindings:<channelName>:group=hdfsWrite or spring:cloud:stream:bindings:<channelName>:group=average.

All groups that subscribe to a given destination receive a copy of published data, but only one member of each group receives a given message from that destination. By default, when a group is not specified, Stream assigns the application service to an anonymous and independent single-member consumer group that is in a publish-subscribe relationship with all other consumer groups.

Durability

As part of the opinionated model, Stream consumer group subscriptions are durable. That is, Binder implementations ensure that group subscriptions are persistent and once a subscription for a group has been created, the group receives messages, even if they are sent while all services in the group have been stopped.

In general, it is preferable to always specify a consumer group when binding a service to a given destination. When scaling up a Stream service, you must specify a consumer group for each of its input bindings. Doing so prevents the service instances from receiving duplicate messages unless that behavior is desired, which is not typical.

Anonymous subscriptions are non-durable by nature. For some Binder implementations (such as RabbitMQ), it is possible to have non-durable group subscriptions as well.

Partitioning Data

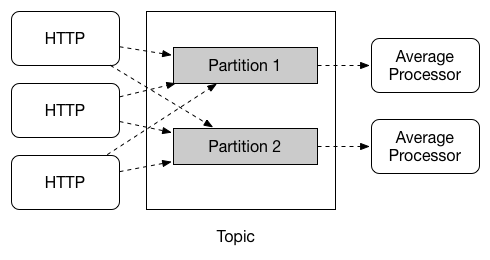

Stream provides support for partitioning data between multiple instances of a given service. In a partitioned scenario, the physical communication medium (such as the broker topic) is viewed as being structured into multiple partitions. One or more producer instances send data to multiple consumer instances and ensure that data identified by common characteristics are processed by the same consumer instance.

Stream provides a common abstraction for implementing partitioned processing use cases in a uniform fashion. Partitioning can thus be used whether the broker itself is naturally partitioned (for example, Kafka) or not (for example, RabbitMQ).

Partitioning is a critical concept in stateful processing, where it is critical, for either performance or consistency reasons, to ensure that all related data is processed together. For example, in the time-windowed average calculation example, it is important that all measurements from any given sensor are processed by the same service instance.

To set up a partitioned processing scenario, you must configure both the data-producing and the data-consuming ends.

Programming Model

To understand the programming model, you need to understand the following core concepts:

- Binder: Component responsible to provide integration with the external messaging systems.

- Binding: Bridge between the external messaging system and application service provided producers and consumers.

- Message: The canonical data structure used by producers and consumers to communicate with binders, and thus other application services via external messaging systems.

Binder

As mentioned earlier, binders are an abstraction used by Steeltoe that enables Stream-based application services to integrate with external messaging systems. This integration includes the responsibility for connectivity, delegation, and routing of messages to and from producers and consumers. It also includes support for data type conversions, invocation of the application code responsible for processing messages, and more. Binders are an infrastructure component provided by Steeltoe or other third party providers.

Binders implement a lot of the boiler-plate code that would otherwise fall on the shoulders of an application developer when communicating with the messaging system. A binder typically requires some form of configuration settings in order to properly function. This detail will be covered in an the upcoming section.

Bindings

As stated earlier, bindings provide the bridge between the external messaging system and application-provided methods which act as producers and consumers.

You can use the EnableBinding attribute in your application to declare bindings for your application or you can use service container extension methods to explicitly add them to the container yourself.

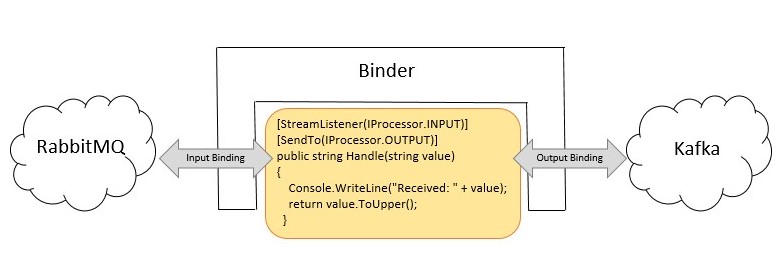

For example the following code shows a fully configured and functioning Stream application service that receives strings from a destination with the name input and

and converts the strings to uppercase and then sends the results to a destination with the name output. Notice that the applications Handle() method expects the message payload from input to be a string, and as a result the Stream framework will attempt to convert the incoming message payload to a string before calling the handler method (see Content Type Negotiation section).

[EnableBinding(typeof(IProcessor))]

public class Program

{

public static async Task Main(string[] args)

{

var host = StreamHost

.CreateDefaultBuilder<Program>(args)

.Build();

await host.StartAsync();

}

[StreamListener(IProcessor.INPUT)]

[SendTo(IProcessor.OUTPUT)]

public string Handle(string value)

{

Console.WriteLine("Received: " + value);

return value.ToUpper();

}

}

If you examine the EnableBinding attribute, you'll see that it takes one or more interface types as parameters. Each interface represents a binding and each method defined in the binding interface represents a bindable (frequently referred to as a destination). Normally, each bindable represents a named message channel when using channel-based binders such as RabbitMQ, Kafka, etc. However, other types of bindings can provide other types of bindables which are intended to support native features of the underlying messaging technology.

Out of the box, Steeltoe provides the three bindings that are commonly used in messaging based services. ISource, ISink, and IProcessor bindings are generic enough that you can use them with many different messaging systems.

- ISink: Defines a contract for a message consumer by providing a destination from which messages are consumed.

- ISource: Defines the contract for a message producer by providing the destination to which the produced message is sent.

- IProcessor: Encapsulates both the

ISinkand theISourcecontracts by exposing two destinations that allow consumption and production of messages.

The following listing shows the definition of the various interfaces:

public interface ISink

{

const string INPUT = "input";

[Input(INPUT)]

ISubscribableChannel Input { get; }

}

public interface ISource

{

const string OUTPUT = "output";

[Output(OUTPUT)]

IMessageChannel Output { get; }

}

public interface IProcessor : ISource, ISink

{

}

Notice in the above the usage of Input and Output attributes on the property getters.

The Input attribute identifies an input channel from which messages received enter the service. Notice that the constructor argument gives it a name and the type of channel is defined by the return type of the getter (ISubscribableChannel).

The Output attribute identifies an output channel, through which messages are published. Again, notice the constructor argument gives it a name and the type of channel is defined by the return type of the getter (ISubscribableChannel).

As you can see, both the Input and Output attributes optionally take a channel name as a constructor parameter. If a name is not provided, the name of the annotated method is used as the channel name.

Steeltoe Stream automatically creates an implementation of the interface for you upon start up and makes it available in the service container. While not a common use case, you can use this in the application service by adding it as a constructor argument to a service you have written. This will give you access to the channel directly via the property getter. This is not a common way of accessing the channel as Steeltoe provides a much easier programming model which is normally used.

While the out-of-the-box bindings satisfy the majority of use cases, you can also create your own contracts by defining your own binding interfaces with the Input and Output attributes identifying the actual bindables.

For example:

public interface IBarista

{

[Input]

ISubscribableChannel Orders { get; }

[Output]

IMessageChannel HotDrinks { get; }

[Output]

IMessageChannel ColdDrinks { get; }

}

Using the interface shown in the preceding example as a parameter to EnableBinding triggers the creation of the three bound channels named Orders, HotDrinks, and ColdDrinks,

respectively.

You can provide as many binding interfaces as you need as arguments to the EnableBinding annotation:

[EnableBinding(typeof(IOrders), typeof(IPayment))]

public class Program {

{

static async Task Main(string[] args)

{

var host = StreamHost

.CreateDefaultBuilder<Program>(args)

.Build();

await host.StartAsync();

}

}

Notice in the above examples the return type of the individual bindables (e.g. interface properties). The bindable return type IMessageChannel is a channel component provided as part of the Steeltoe Messaging infrastructure for interfacing with outbound destinations. The ISubscribableChannel is also provided by Steeltoe Messaging and is used for inbound message reception.

The above bindings support event-based message consumption but sometimes you need more control of the interactions with the messaging infrastructure(e.g. rate of consumption). So instead of using a ISubscribableChannel channel, you can instead use a pollable message source, IPollableMessageSource.

The following example shows how to define a pollable binding.

public interface IPolledBarista {

[Input]

IPollableMessageSource Orders { get; }

}

In this case, an implementation of IPollableMessageSource is bound to the channel with the name Orders. See Using Polled Consumers for more details.

As mentioned earlier the Input and Output attributes allow you to specify a customized channel name for the channel, as shown in the following example:

public interface IBarista

{

[Input("InboundOrders")]

ISubscribableChannel Orders { get; }

}

In the above example the created channel is named InboundOrders.

Normally, you do not need to access the individual channels or bindings directly, however there may be times (such as testing or other corner cases) when you do.

Aside from generating channels for each binding and registering them as services in the container, Steeltoe Stream also generates a service that implements the interface. That means you can have access to the interfaces representing the bindings or individual channels by injecting the binding interface into your application component.

Producing and Consuming Messages

The easiest way to write a a Steeltoe Stream application service is by using Steeltoe Stream attributes.

StreamListener Attribute

Steeltoe Stream provides a StreamListener attribute, modeled after other Steeltoe Messaging annotations (e.g. RabbitListener, and others) and supports features such as content-based routing and others.

static async Task Main(string[] args)

{

var host = StreamHost

.CreateDefaultBuilder<VoteHandler>(args)

.ConfigureServices(svc=> svc.AddSingleton<IVotingService, DefaultVotingService>())

.Build();

await host.StartAsync();

}

[EnableBinding(typeof(ISink))]

public class VoteHandler

{

private readonly IVotingService votingService;

public VoteHandler(IVotingService service)

{

votingService = service;

}

[StreamListener(ISink.INPUT)]

public void Handle(Vote vote)

{

votingService.Record(vote);

}

}

As with other Steeltoe Messaging methods, method arguments can be annotated with Payload, Headers, and Header to enable access to additional content from the underlying message.

For methods that return data, you must use the SendTo attribute to specify the output destination for data returned by the method, as shown in the following example:

public class Program

{

static async Task Main(string[] args)

{

var host = StreamHost

.CreateDefaultBuilder<TransformProcessor>(args)

.ConfigureServices(svc=> svc.AddSingleton<IVotingService, DefaultVotingService>())

.Build();

await host.StartAsync();

}

[EnableBinding(typeof(IProcessor))]

public class TransformProcessor

{

private readonly IVotingService votingService;

public TransformProcessor(IVotingService service)

{

votingService = service;

}

[StreamListener(IProcessor.INPUT)]

[SendTo(IProcessor.OUTPUT)]

public VoteResult Handle(Vote vote)

{

return votingService.Record(vote);

}

}

}

StreamListener and Content-based Routing

Steeltoe Stream supports dispatching messages to multiple handler methods annotated with StreamListener based on conditions.

In order to be eligible to support conditional dispatching, the annotated method must not return a value;

The condition is specified using an expression in the Condition argument of the annotation and is evaluated for each message.

All the handlers that match the condition are invoked in the same thread, and no assumption should be made about the order in which the invocations take place.

In the following example of a StreamListener with dispatching conditions, all the messages bearing a header with the key type equal to the value bogey are dispatched to the

ReceiveBogey method, and all the messages bearing a header type with the value bacall are dispatched to the ReceiveBacall method.

public class Program

{

static async Task Main(string[] args)

{

var host = StreamHost

.CreateDefaultBuilder<CatsAndDogs>(args)

.Build();

await host.StartAsync();

}

[EnableBinding(typeof(IProcessor))]

public class CatsAndDogs

{

[StreamListener(ISink.INPUT, "Headers['type']=='Dog'")]

public void Handle(Dog dog)

{

Console.WriteLine("Dog says:"+ dog.Bark);

}

[StreamListener(ISink.INPUT, "Headers['type']=='Cat'")]

public void Handle(Cat cat)

{

Console.WriteLine("Cat says:" +cat.Meow);

}

}

}

It is important to understand some of the mechanics behind content-based routing using the Condition property of StreamListener, especially in the context of the type of the message as a whole.

It may also help if you familiarize yourself with the Content Type Negotiation before you proceed.

Consider the following example:

The code below is perfectly valid. It compiles and deploys without any issues, yet it never produces the result you expect.

public class Program

{

static async Task Main(string[] args)

{

var host = StreamHost

.CreateDefaultBuilder<CatsAndDogs>(args)

.Build();

await host.StartAsync();

}

}

[EnableBinding(typeof(IProcessor))]

public class CatsAndDogs

{

[StreamListener(Target = Sink.INPUT, Condition = "Payload.GetType().Name=='Dog'")]

public void Bark(Dog dog)

{

// handle the message

}

[StreamListener(Target = Sink.INPUT, Condition = "Payload.GetType().Name=='Cat'")]

public void Purr(Cat cat)

{

// handle the message

}

}

The intent of the expression in the Condition is to reference in the incoming Payload from the message and access the Type of the object returned and then route based on whether the objects type is a Dog or a Cat.

The reason this does not work is because at this point the expression is testing something that does not yet exist in the message that is being processed. At this point in processing of an incoming message the payload has not yet been converted from the

wire format, typically a byte[], to the desired type exposed in the methods signature. In other words, it has not yet gone through the type conversion process described in the Content Type Negotiation.

Polled Consumers

When implementing polled consumers, you are required to poll the IPollableMessageSource on demand.

Consider the following example of a polled consumer:

public interface IPolledConsumerBinding

{

[Input]

IPollableMessageSource DestIn { get; }

[Output]

IMessageChannel DestOut { get; }

}

[EnableBinding(typeof(IPolledConsumerBinding))]

public class Program

{

static async Task Main(string[] args)

{

var host = StreamHost

.CreateDefaultBuilder<Program>(args)

.ConfigureServices(svc => svc.AddHostedService<Worker>())

.Build();

await host.StartAsync();

}

}

Given the polled consumer in the preceding example, you might use it as follows:

public class Worker : BackgroundService, IMessageHandler

{

private readonly IPolledConsumerBinding _binding;

private readonly ILogger<Worker> _logger;

public string ServiceName { get; set; } = "BackgroundWorker";

public Worker(IPolledConsumerBinding binding, ILogger<Worker> logger)

{

_binding = binding;

_logger = logger;

}

protected override async Task ExecuteAsync(CancellationToken stoppingToken)

{

await Task.Delay(5000, stoppingToken); // Wait for setup on first poll

while (!stoppingToken.IsCancellationRequested)

{

_logger.LogInformation("Worker running at: {time}", DateTimeOffset.Now);

try

{

if (!_binding.DestIn.Poll(this))

{

await Task.Delay(2000, stoppingToken);

}

}

catch (Exception e)

{

_logger.LogError(e, e.Message);

}

}

}

public void HandleMessage(IMessage message)

{

try

{

var payloadString = (string)message.Payload;

var newPayload = payloadString.ToUpper();

_logger.LogInformation("Received Message : " + payloadString);

_binding.DestOut.Send(Message.Create(newPayload));

_logger.LogInformation("Sent Message : " + newPayload);

}

catch (Exception e)

{

_logger.LogError(e, e.Message);

}

}

}

The IPollableMessageSource.Poll() method takes a IMessageHandler argument. It returns True if a message was received and successfully processed.

As with message-driven consumers, if the IMessageHandler throws an exception, messages are published to error channels, as discussed in Error Handling.

Normally, the Poll() method acknowledges the message when the IMessageHandler exits. If the method exits abnormally, the message is rejected and not re-queued, but see Handling Errors for more options.

You can override that behavior by taking responsibility for the acknowledgment, as shown in the following example:

public void HandleMessage(IMessage message)

{

try

{

StaticMessageHeaderAccessor.GetAcknowledgmentCallback(message).IsAutoAck = False;

// e.g. hand off to another thread which can perform the ack or Acknowledge(Status.REQUEUE)

}

catch (Exception e)

{

// handle failure

}

}

IMPORTANT: You must

ack(ornack) the message at some point, to avoid resource leaks.

IMPORTANT: Some messaging systems maintain a simple offset in a log. If a delivery fails and is re-queued with

StaticMessageHeaderAccessor.GetAcknowledgmentCallback(m).Acknowledge(Status.REQUEUE);, any later successfully ack'd messages are redelivered.

There is also an overloaded Poll method which allows you to provide a conversion hint:

Poll(IMessageHandler handler, Type type)

The type is a conversion hint that allows the incoming message payload to be converted, as shown in the following example:

....

protected override async Task ExecuteAsync(CancellationToken stoppingToken)

{

while (!stoppingToken.IsCancellationRequested)

{

_logger.LogInformation("Worker running at: {time}", DateTimeOffset.Now);

try

{

if (!_binding.DestIn.Poll(this), typeof(Dictionary<string, Foo>))

{

await Task.Delay(1000, stoppingToken);

}

}

catch (Exception e)

{

// handle failure

}

}

}

public void HandleMessage(IMessage message)

{

try

{

var payload = ((Dictionary<string, Foo>) message.Payload);

....

}

catch (Exception e)

{

// handle failure

}

}

By default, an error channel is configured for the pollable source. If the callback throws an exception an ErrorMessage is sent to the error channel with the name(<destination>.<group>.errors).

You can subscribe to the error channel with a ServiceActivator attribute to receive and process the ErrorMessage. Without a subscription, the error will simply be logged and the message will be acknowledged as successful.

If the error channel service activator throws an exception, the message will be rejected (by default) and won't be redelivered.

If the service activator throws a RequeueCurrentMessageException, the message will be requeued at the broker and will be again retrieved on a subsequent poll.

If the handler throws a RequeueCurrentMessageException directly, the message will be requeued, as discussed above, and will not be sent to the error channel.

Error Handling

Errors happen and Steeltoe Stream provides several flexible mechanisms to handle them. The error handling comes in two flavors:

- application: The error handling is done within the application service using a custom error handler.

- system: The error handling is delegated to the binder to handle by re-queueing, or using a DL queue or via some other means. Note that the techniques are dependent on binder implementation and the capability of the underlying messaging middleware.

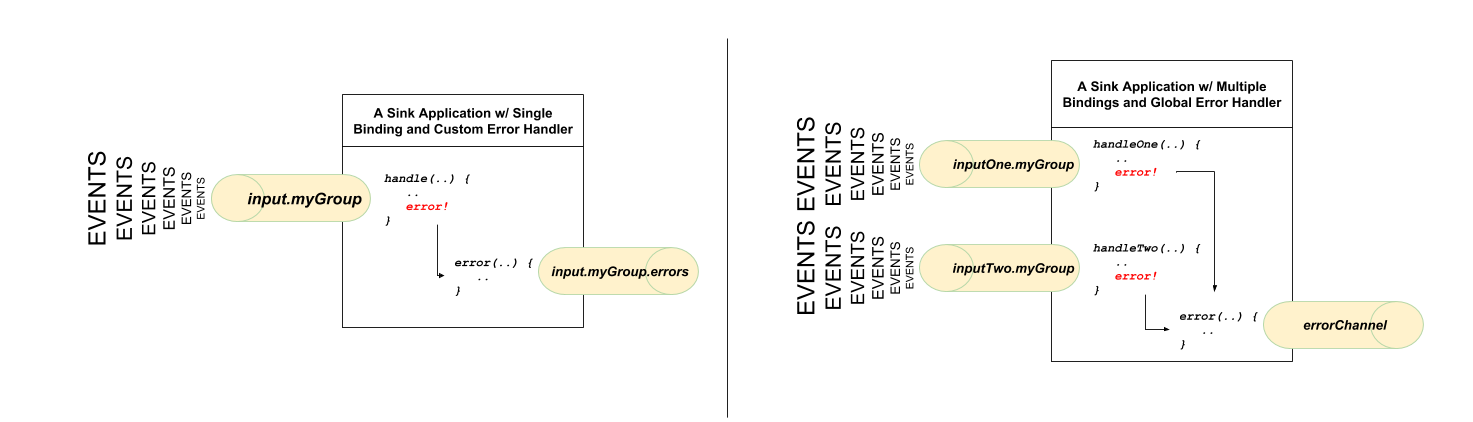

Application Error Handling

There are two types of application-level error handling. Errors can be handled at each binding subscription or by a global handler which handles all the binding errors. Below are the details.

For each input binding, Steeltoe Stream creates a dedicated error channel with the following name <destinationName>.errors.

The

<destinationName>consists of the name of the binding bindable name (e.g.input) and the name of the group (e.g.myGroup).

Consider the following:

spring:cloud:stream:bindings:input:group=myGroup

[StreamListener(ISink.INPUT)] // destination name 'input.myGroup'

public void Handle(Person value)

{

throw new Exception("BOOM!");

}

[ServiceActivator(IProcessor.INPUT + ".myGroup.errors")] //channel name 'input.myGroup.errors'

public void Error(IMessage message)

{

Console.WriteLine("Handling ERROR: " + message);

}

In the preceding example the destination name is input.myGroup and the dedicated error channel name is input.myGroup.errors.

NOTE: The use of

StreamListenerannotation is intended specifically to define bindings that bridge internal channels and external destinations. TheServiceActivatorannotation is used to reference internally created channels.

NOTE: If

groupis not specified, an anonymous group is used instead (e.g.input.anonymous.2K37rb06Q6m2r51-SPIDDQ). This is obviously not suitable for error handling scenarios, since you don't know what the name is going to be until the destination is created.

If you have multiple bindings, you may want to have a single error handler for all of them. Steeltoe Stream automatically provides support for

a global error channel by bridging each individual error channel to the channel named errorChannel, allowing a single subscriber to handle all errors as shown in the following example:

[ServiceActivator("errorChannel")]

public void Error(IMessage message)

{

Console.WriteLine("Handling ERROR: " + message);

}

This may be a convenient option if error handling logic is the same regardless of which handler produced the error.

System Error Handling

System-level error handling implies that the errors are communicated back to the messaging system and given that not every messaging system is the same, the capabilities may differ from binder to binder.

That said, in this section we explain the general idea behind system level error handling and using the RabbitMQ binder as an example. For more details and configuration options, see the individual binder's documentation.

If no internal error handlers are configured, the errors propagate to the binders, and the binders subsequently propagate those errors back to the messaging system. Depending on the capabilities of the messaging system, some may drop the message, re-queue the message for re-processing or _send the failed message to Dead Letter Queue (DLQ). The RabbitMQ binder support these concepts. However, other binders may not, so refer to your individual binder’s documentation for details on supported system-level error-handling options.

Drop Failed Messages

By default, if no additional system-level configuration is provided, the messaging system drops the failed message. While acceptable in some cases, for most cases, it is not, and we need some recovery mechanism to avoid message loss.

Dead Letter Queue (DLQ)

DLQ allows failed messages to be sent to a special destination: - Dead Letter Queue.

When configured, failed messages are sent to this destination for subsequent re-processing or auditing and/or reconciliation.

For example, continuing on the previous example and to set up the DLQ with RabbitMQ binder, you need to set the following configuration setting:

spring:cloud:stream:rabbit:bindings:input:consumer:autoBindDlq=True

Keep in mind that, in the above setting, input corresponds to the name of the input destination binding.

The consumer indicates that it is a consumer property and autoBindDlq instructs the binder to configure the DLQ for the input destination, which results in an additional Rabbit queue named input.myGroup.dlq.

Once configured, all failed messages are routed to this queue with an error message similar to the following:

delivery_mode: 1

headers:

x-death:

count: 1

reason: rejected

queue: input.hello

time: 1522328151

exchange:

routing-keys: input.myGroup

Payload {"name”:"Bob"}

As you can see from the above, your original message is preserved for further actions.

However, one thing you may have noticed is that there is limited information on the original issue with the message processing. For example, you do not see a stack trace corresponding to the original error. To get more relevant information about the original error, you must set an additional configuration setting:

spring:cloud:stream:rabbit:bindings:input:consumer:republishToDlq=True

Doing so forces the internal error handler to intercept the error message and add additional information to it before publishing it to DLQ. Once configured, you can see that the error message contains more information relevant to the original error, as follows:

delivery_mode: 2

headers:

x-original-exchange:

x-exception-message: has an error

x-original-routingKey: input.myGroup

x-exception-stacktrace: <The stack trace captured during the error>

Payload {"name”:"Bob"}

This effectively combines application-level and system-level error handling to further assist with downstream troubleshooting mechanics.

Re-queue Failed Messages

Currently supported binders rely on an internal class called a RetryTemplate to facilitate successful message processing. The template is configurable and will attempt to deliver messages to the consumer/handler and retry up to a max number of attempts if not successful. See the section which follow for configuration parameters. However, for cases when the maxAttempts configuration setting is set to 1, internal reprocessing of the message is disabled. To facilitate message re-processing (re-tries) under this condition you can instead

instruct the messaging system to re-queue the failed message to be reprocessed. Once re-queued, the failed message is sent back to the original handler, essentially creating a retry loop.

This configuration option may be feasible for cases where the nature of the error is related to some sporadic yet short-term unavailability of some resource.

To accomplish that, you must set the following configuration settings:

spring:cloud:stream:bindings:input:consumer:maxAttempts=1

spring:cloud:stream:rabbit:bindings:input:consumer:requeueRejected=True

With these settings the failed message is resubmitted to the same handler and loops continuously or until the handler throws RabbitRejectAndDontRequeueException

essentially allowing you to build your own re-try logic within the handler itself.

Retry Template

The RetryTemplate is part of the Steeltoe library and is used internally for various purposes.

While it is out of scope of this document to cover all of the capabilities of the RetryTemplate, we will mention the following consumer properties that are specifically related to

the RetryTemplate:

maxAttempts The number of attempts to process the message.

Default: 3.

backOffInitialInterval The back-off initial interval on retry.

Default 1000 milliseconds.

backOffMaxInterval The maximum back-off interval.

Default 10000 milliseconds.

backOffMultiplier The back-off multiplier.

Default 2.0.

defaultRetryable

Whether exceptions thrown by the consumer that are not listed in the retryableExceptions are retryable.

Default: True.

retryableExceptions

A list of Exception class names.

Specify those exceptions (and subclasses) that will be retried.

Also see defaultRetryable.

Default: empty.

Binders

Steeltoe Stream provides a Binder abstraction for use in connecting to physical destinations at the external middleware. This section provides information about the main concepts behind the Binder SPI, its main components, and implementation-specific details. This section is relevant to those developers who might be considering developing a binder for a specific messaging platform.

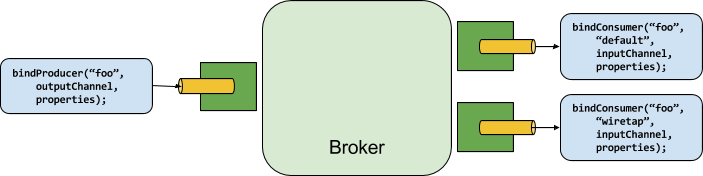

Producers and Consumers

The following image shows the general relationship of producers and consumers:

A producer is any component that sends messages to a channel.

The channel can be bound to an external message broker with a binder implementation for that broker.

When invoking the BindProducer() method, the first parameter is the name of the destination within the broker, the second parameter is the local channel instance to which the producer sends messages, and the third parameter contains properties (such as a partition key expression) to be used within the adapter that is created for that channel.

A consumer is any component that receives messages from a channel.

As with a producer, the consumer's channel can be bound to an external message broker.

When invoking the BindConsumer() method, the first parameter is the destination name, and a second parameter provides the name of a logical group of consumers.

Each group that is represented by consumer bindings for a given destination receives a copy of each message that a producer sends to that destination (that is, it follows normal publish-subscribe semantics).

If there are multiple consumer instances bound with the same group name, then messages are load-balanced across those consumer instances so that each message sent by a producer is consumed by only a single consumer instance within each group (that is, it follows normal queueing semantics).

Binder SPI

The Binder SPI consists of a number of interfaces, out-of-the box utility classes, and discovery strategies that provide a pluggable mechanism for connecting to external middleware.

The key point of the SPI is the IBinder interface(s), which is a strategy for connecting inputs and outputs to external middleware. The following listing shows the definition of the IBinder interface:

public interface IBinder : IServiceNameAware

{

Type TargetType { get; }

IBinding BindConsumer(string name, string group, object inboundTarget, IConsumerOptions consumerOptions);

IBinding BindProducer(string name, object outboundTarget, IProducerOptions producerOptions);

}

public interface IBinder<in T> : IBinder

{

IBinding BindConsumer(string name, string group, T inboundTarget, IConsumerOptions consumerOptions);

IBinding BindProducer(string name, T outboundTarget, IProducerOptions producerOptions);

}

The interface is parameterized, offering a number of extension points:

- Input and output bind targets. Typically an

IMessageChannelis supported, but this is intended to be used as an extension point in the future. - Consumer and producer options, allowing specific Binder implementations to add supplemental properties that can be supported in a type-safe manner.

A typical binder implementation consists of the following:

- A class that implements the

IBinder<T>interface; - A assembly level

BinderAttributedefining the name of the binder and the System.Type that will be used to configure the binder upon startup. - A startup class which has contains a constructor that takes an

IConfigurationas an argument and a method with the nameConfigureServices()and takes a single argumentIServiceCollection.

Here is an example of the 'startup class'

[assembly: Binder("testbinder", typeof(Startup))]

public class Startup

{

public Startup(IConfiguration configuration)

{

Configuration = configuration;

}

public IConfiguration Configuration { get; }

// This method gets called by the runtime. Use this method to configure the service container for the binder

public void ConfigureServices(IServiceCollection services)

{

....

}

}

Binder Detection

The Steeltoe Stream infrastructure relies on implementations of the Binder SPI to perform the task of connecting channels to message brokers. Each Binder implementation typically connects to one type of messaging system.

By default, the Stream infrastructure will auto-configure the binder by searching for the assembly BinderAttribute in each assembly located in the directory from which the application is started.

If a single Binder implementation is found, Steeltoe Stream automatically uses it and configures it using the ConfigureServices() method illustrated above.

For example, a Stream project that aims to bind only to RabbitMQ can add the following dependency to the project.

<PackageReference Include="Steeltoe.Stream.Binder.RabbitMQ" Version="3.2.0" />

Multiple Binders

When multiple binders are discovered, the application must indicate which binder is to be used for each channel binding.

Each assembly BinderAttribute discovered contains the name of the binder that should be used when configuring channel bindings.

Binder selection can either be performed globally, using the spring:cloud:stream:defaultBinder configuration key (for example, spring:cloud:stream:defaultBinder=rabbit) or individually, by configuring the binder on each channel binding.

For instance, an application that has channels named input and output for read and write operations and needs to read from a binder with name foo and write to RabbitMQ can specify the following configuration:

spring:cloud:stream:bindings:input:binder=foo

spring:cloud:stream:bindings:output:binder=rabbit

Binder Configuration

The following settings are available when customizing binder configurations. These settings can be obtained by binding an IConfiguration to Steeltoe.Stream.Config.BinderOptions

They must be prefixed with spring:cloud:stream:binders.<binderName>.

type

The binder type. It typically references one of the binders found during discovery of the assembly BinderAttribute attributes.

By default, it has the same value as the configuration name.

inheritEnvironment Whether the configuration inherits the environment of the application itself.

Default: True.

environment Root for a set of properties that can be used to customize the environment of the binder. When this property is set, the configuration in which the binder is being created is not a the application configuration. This setting allows for complete separation between the binder components and the application components.

Default: empty.

defaultCandidate Whether the binder is a candidate for being considered a default binder or can be used only when explicitly referenced. This setting allows adding a binder without interfering with the default processing.

Default: True.

Configuration Settings

Steeltoe Stream supports general configuration settings as well as configuration for bindings and binders. Some binders let additional binding properties support middleware-specific features.

Configuration settings can be provided to Stream applications through any mechanism supported by .NET. This includes application arguments, environment variables, and JSON files.

Binding Service Settings

These settings can be obtained by binding an IConfiguration to Steeltoe.Stream.Config.BindingServiceOptions. All settings should be prefixed with spring:cloud:stream.

instanceCount

The expected number of deployed instances of an application.

Must be set for partitioning on the producer side. Must be set on the consumer side when using RabbitMQ and if autoRebalanceEnabled=False.

Default: 1.

instanceIndex

The instance index of the application: A number from 0 to instanceCount - 1.

Used for partitioning with RabbitMQ if autoRebalanceEnabled=False.

Automatically set in TAS to match the application's instance index.

dynamicDestinations A list of destinations that can be bound dynamically (for example, in a dynamic routing scenarios). If set, only listed destinations can be bound.

Default: empty (letting any destination be bound).

defaultBinder The default binder to use, if multiple binders are discovered. See Multiple Binders.

Default: empty.

overrideCloudConnectors

If the setting is False (the default), the binder detects a suitable bound service (for example, a RabbitMQ service bound in Cloud Foundry for the RabbitMQ binder) and uses it for creating connections (usually through Steeltoe Connectors).

When set to True, this setting instructs binders to completely ignore the bound services and rely on applications configuration (for example, relying on the spring:rabbitmq.* properties provided in the configuration for the RabbitMQ binder).

The typical usage of this setting is to be nested in a customized environment.

Default: False.

bindingRetryInterval The interval (in seconds) between retrying binding creation when, for example, the binder does not support late binding and the broker is down. Set it to zero to treat such conditions as fatal, preventing the application from starting.

Default: 30

Binding Settings

Binding settings are supplied by using the format of spring:cloud:stream:bindings:<channelName>:<setting>=<value>.

The <channelName> represents the name of the channel being configured (for example, output for a Source).

To avoid repetition, Stream supports setting values for all channels, in the format of spring:cloud:stream:default:<setting>=<value> for common binding properties, and spring:cloud:stream:default:<producer|consumer>.<setting>=<value>.

When it comes to avoiding repetitions for extended binding properties, this format should be used - spring:cloud:stream:<binder-type>:default:<producer|consumer>.<setting>=<value>.

In what follows, we indicate where we have omitted the spring:cloud:stream:bindings:<channelName>. prefix and focus just on the setting name, with the understanding that the prefix ise included at runtime.

Common Binding Settings

These settings can be obtained by binding an IConfiguration to Steeltoe.Stream.Config.BindingOptions.

The following binding settings are available for both input and output bindings and must be prefixed with spring:cloud:stream:bindings:<channelName>. (for example, spring:cloud:stream:bindings:input:destination=ticktock).

Default values can be set by using the spring:cloud:stream:default prefix (for examplespring:cloud:stream:default:contentType=application/json).

destination

The target destination of a channel on the bound middleware (for example, the RabbitMQ exchange).

If the channel is bound as a consumer, it could be bound to multiple destinations, and the destination names can be specified as comma-separated string values.

If not set, the channel name is used instead.

The default value of this property cannot be overridden.

group The consumer group of the channel. Applies only to inbound bindings. See Consumer Groups.

Default: null (indicating an anonymous consumer).

contentType The content type of the channel. See Content Type Negotiation.

Default: application/json.

binder The binder used by this binding. See Multiple Binders for details.

Default: null (the default binder is used, if it exists).

Consumer Settings

These settings can be obtained by binding an IConfiguration to Steeltoe.Stream.Config.ConsumerOptions.

The following binding settings are available for input bindings only and must be prefixed with spring:cloud:stream:bindings:<channelName>.consumer. (for example, spring:cloud:stream:bindings:input:consumer:concurrency=3).

Default values can be set by using the spring:cloud:stream:default:consumer prefix (for example, spring:cloud:stream:default:consumer:headerMode=none).

autoStartup Signals if this consumer needs to be started automatically

Default: True.

concurrency The concurrency of the inbound consumer.

Default: 1.

partitioned Whether the consumer receives data from a partitioned producer.

Default: False.

headerMode

When set to None, disables header parsing on input.

Effective only for messaging middleware that does not support message headers natively and requires header embedding.

This option is useful when consuming data from non-Stream applications when native headers are not supported.

When set to Headers, it uses the middleware's native header mechanism.

When set to EmbeddedHeaders, it embeds headers into the message payload.

Default: depends on the binder implementation.

maxAttempts

If processing fails, the number of attempts to process the message (including the first).

Set to 1 to disable retry.

Default: 3.

backOffInitialInterval The back-off initial interval on retry.

Default: 1000.

backOffMaxInterval The maximum back-off interval.

Default: 10000.

backOffMultiplier

The back-off multiplier.

Default: 2.0.

defaultRetryable

Whether exceptions thrown by the listener that are not listed in the retryableExceptions are retryable.

Default: True.

instanceIndex

When set to a value greater than equal to zero, it allows customizing the instance index of this consumer (if different from spring:cloud:stream:instanceIndex).

When set to a negative value, it defaults to spring:cloud:stream:instanceIndex.

Default: -1.

instanceCount

When set to a value greater than equal to zero, it allows customizing the instance count of this consumer (if different from spring:cloud:stream:instanceCount).

When set to a negative value, it defaults to spring:cloud:stream:instanceCount.

Default: -1.

retryableExceptions

A comma separated list of Exception class names.

Specify those exceptions (and subclasses) that will be retried.

Also see defaultRetryable.

Default: empty.

useNativeDecoding

When set to True, the inbound message is deserialized directly by the client library, which must be configured correspondingly.

When this configuration is being used, the inbound message unmarshalling is not based on the contentType of the binding.

When native decoding is used, it is the responsibility of the producer to use an appropriate encoder to serialize the outbound message.

Also, when native encoding and decoding is used, the headerMode=EmbeddedHeaders setting is ignored and headers are not embedded in the message.

See the producer property useNativeEncoding.

Default: False.

Advanced Consumer Binding Settings

For advanced configuration of the underlying message listener container for message-driven consumers see the documentation for the binder you expect to use.

Producer Settings

These settings can be obtained by binding an IConfiguration to Steeltoe.Stream.Config.ProducerOptions.

The following binding settings are available for output bindings only and must be prefixed with spring:cloud:stream:bindings:<channelName>.producer. (for example, spring:cloud:stream:bindings:input:producer:partitionKeyExpression=payload.id).

Default values can be set by using the prefix spring:cloud:stream:default:producer (for example, spring:cloud:stream:default:producer:partitionKeyExpression=payload.id).

autoStartup Signals if this consumer needs to be started automatically

Default: True.

partitionKeyExpression

An expression that determines how to partition outbound data.

If set, outbound data on this channel is partitioned. partitionCount must be set to a value greater than 1 to be effective.

See Partitioning Support.

Default: null.

partitionSelectorExpression

An expression for customizing partition selection.

If not set, the partition is selected as the GetHashCode(key) % partitionCount, where key is computed through partitionKeyExpression.

Default: null.

partitionKeyExtractorName

The name of a .NET type that implements IPartitionKeyExtractorStrategy. It will be used to extract a key used to compute

the partition id (see 'partitionSelector*'). Mutually exclusive with 'partitionKeyExpression'.

Default: null.

partitionSelectorName

The name of a .NET type that implements IPartitionSelectorStrategy. It will be used to determine partition id based

on partition key (see 'partitionKeyExtractor*'). Mutually exclusive with 'partitionSelectorExpression'.

Default: null.

partitionCount The number of target partitions for the data, if partitioning is enabled. Must be set to a value greater than 1 if the producer is partitioned.

Default: 1.

requiredGroups A comma-separated list of groups to which the producer must ensure message delivery even if they start after it has been created (for example, by pre-creating durable queues in RabbitMQ).

headerMode

When set to None, it disables header embedding on output.

It is effective only for messaging middleware that does not support message headers natively and requires header embedding.

This option is useful when producing data for non-Stream applications when native headers are not supported.

When set to Headers, it uses the middleware's native header mechanism.

When set to EmbeddedHeaders, it embeds headers into the message payload.

Default: Depends on the binder implementation.

useNativeEncoding

When set to True, the outbound message is serialized directly by the client library, which must be configured correspondingly.

When this configuration is being used, the outbound message marshalling is not based on the contentType of the binding.

When native encoding is used, it is the responsibility of the consumer to use an appropriate decoder to deserialize the inbound message.

Also, when native encoding and decoding is used, the headerMode=EmbeddedHeaders setting is ignored and headers are not embedded in the message.

See the consumer setting useNativeDecoding.

Default: False.

errorChannelEnabled

When set to True, if the binder supports asynchronous send results, send failures are sent to an error channel for the destination.

See Error Handling for more information.

Default: False.

Dynamically Bound Destinations

Besides the channels defined by using EnableBinding attribute, Stream lets applications send messages to dynamically bound destinations.

This is useful, for example, when the target destination needs to be determined at runtime.

Applications can do so by using the BinderAwareChannelResolver service (which is registered automatically when using AddStreamServices<T> extension in the application Host Builder).

The spring.cloud.stream.dynamicDestinations setting can be used for restricting the dynamic destination names to a known set (whitelisting).

If this property is not set, any destination can be bound dynamically.

The BinderAwareChannelResolver can be used directly, as shown in the following example of a console application receiving messages from an input source and deciding the target channel based on the body of the message (see Dynamic Destination Sample for full solution):

Program.cs

[EnableBinding(typeof(ISink))]

class Program

{

private static BinderAwareChannelResolver binderAwareChannelResolver;

static async Task Main(string[] args)

{

var host = StreamHost.CreateDefaultBuilder<Program>(args).Build();

binderAwareChannelResolver =

host.Services.GetService<IDestinationResolver<IMessageChannel>>() as BinderAwareChannelResolver;

await host.StartAsync();

}

[StreamListener(ISink.INPUT)]

public async void Handle(string incomingMessage)

{

var destination = incomingMessage.Contains("URGENT") ? "requests.urgent" : "requests.general";

var outgoingMessage = Message.Create(Encoding.UTF8.GetBytes(incomingMessage));

await binderAwareChannelResolver.ResolveDestination(destination).SendAsync(outgoingMessage);

}

}

appsettings.json

{

"spring": {

"cloud": {

"stream": {

"binder": "rabbit",

"bindings": {

"input": {

"group": "requests",

"destination": "requests.incoming"

}

}

}

}

}

}

Now consider what happens when we start the application and make the following requests from the requests.incoming exhange within RabbitMQ.

The destinations, 'requests.urgent' and 'requests.general', are created in the broker (in the exchange for RabbitMQ) with names of 'requests.urgent' and 'requests.general', and the data is published to the appropriate destinations.

Content Type Negotiation

Data transformation is one of the core features of any message-driven microservice architecture. Given that, in Steeltoe Stream, data is represented as a Steeltoe IMessage, and may be transformed to a desired shape or size before reaching its destination. This is typically required for two reasons:

To convert the contents of the incoming message to match the signature of the application-provided handler method.

To convert the contents of the outgoing message to the wire format required by the underlying messaging system.

The wire format is typically byte[] (that is true for the RabbiMQt binder), but it is governed by the binder implementation in use.

In Steeltoe Stream, message transformation is accomplished with an Steeltoe.Messaging.Converter.IMessageConverter.

Overview

To better understand the mechanics and the necessity behind content-type negotiation, we take a look at a very simple use case by using the following message handler as an example:

[StreamListener(IProcessor.INPUT)]

[SendTo(IProcessor.OUTPUT)]

public string Handle(Person person)

{

....

}

The handler shown above expects a Person object as an argument and produces a string type as an output.

In order for the framework to succeed in passing the incoming IMessage as an argument to this handler, it has to somehow transform the payload of the IMessage type from the wire format to a Person type.

In other words, the framework must locate and apply the appropriate IMessageConverter.

To accomplish that, the framework needs some instructions from the user.

One of these instructions is already provided by the signature of the handler method itself (Person type).

Consequently, in theory, that should be (and, in some cases, is) enough.

However, for the majority of use cases, in order to select the appropriate IMessageConverter, the framework needs an additional piece of information.

That missing piece is contentType of the incoming message.

Steeltoe Stream provides three mechanisms to define contentType (in order of precedence):

HEADER: The

contentTypecan be communicated through theIMessageitself. By providing acontentTypeheader, you declare the content type to use when locating and applying the appropriateIMessageConverter.BINDING: The

contentTypecan be set per destination binding by setting thespring:cloud:stream:bindings:input:content-typesetting.

NOTE: The

inputsegment in the setting key corresponds to the actual name of the destination (which isinputin our case). This approach lets you declare, on a per-binding basis, the content type to use to locate and apply the appropriateIMessageConverter.

- DEFAULT: If

contentTypeis not present in theIMessageheader or the binding, the defaultapplication/jsoncontent type is used to locate and apply the appropriateIMessageConverter.

As mentioned earlier, the preceding list also demonstrates the order of precedence in case of a tie. For example, a header-provided content type takes precedence over any other content type. The same applies for a content type set on a per-binding basis, which essentially lets you override the default content type. However, it also provides a sensible default.

Another reason for making application/json the default stems from the interoperability requirements driven by distributed microservices architectures, where producer and consumer may run on different runtimes (e.g. Java, .NET, etc.).

When the non-void handler method returns, if the the return value is already a IMessage, that IMessage becomes the payload. However, when the return value is not a IMessage, a new IMessage is constructed with the return value as the payload while inheriting

headers from the input IMessage minus the headers defined or filtered by SpringIntegrationOptions.MessageHandlerNotPropagatedHeaders.

By default, there is only one header set in MessageHandlerNotPropagatedHeaders, contentType. This means that the new IMessage does not have contentType header set, thus ensuring that the contentType can evolve.

You can always opt out of returning a IMessage from the handler method where you can inject any header you wish.

Content Type vs Argument Type

As mentioned earlier, for the framework to select the appropriate IMessageConverter, it requires argument type and, optionally, content type information.

The logic for selecting the appropriate IMessageConverter resides with the argument resolvers (IHandlerMethodArgumentResolver) in use by the application and trigger right before the invocation of the user-defined handler method (which is when the actual argument type is known to the framework).

If the argument type of the handler method does not match the type of the current payload, the framework delegates to a stack of pre-configured IMessageConverters to see if any one of them can convert the payload.

If you look at the the method object FromMessage(IMessage message, Type targetClass); of the IMessageConverter you see it takes targetClass as one of its arguments to indicate what Type of result it would like.

The framework also ensures that the provided IMessage always contains a contentType header.

When no contentType header is present, it injects either the per-binding contentType header or the default contentType header.

The combination of contentType together with the argument type is the mechanism by which framework determines if message can be converted to a target type.

If no appropriate IMessageConverter is found, an exception is thrown, which you can handle by adding a custom IMessageConverter.

If the payload type matches the target type declared by the handler method, then there is nothing to convert, and the

payload is passed unmodified. While this sounds pretty straightforward and logical, keep in mind handler methods that take a IMessage or object as an argument you essentially forfeit the conversion process.

NOTE: Do not expect IMessage to be converted into some other type based only on the contentType.

Remember that the contentType is complementary to the target type.

If you wish, you can provide a hint, which IMessageConverter may or may not take into consideration depending on the converter in use.

Message Converters

IMessageConverters define three methods:

object FromMessage(IMessage message, Type targetClass);

T FromMessage<T>(IMessage message);

IMessage ToMessage(object payload, IMessageHeaders headers);

It is important to understand the contract of these methods and their usage, specifically in the context of Stream.

The FromMessage methods convert an incoming IMessage to an expected type.

The payload of the IMessage could be any type, and it is up to the actual implementation of the IMessageConverter to support multiple types.

For example, some JSON converter may support the payload type as byte[], string, or others.

However, the ToMessage method has a more strict contract and must always convert the payload and headers to the wire format required of the underlying message infrastructure, typically a byte[].

Provided MessageConverters

As mentioned earlier, the framework already provides a stack of IMessageConverters to handle most common use cases.

The following list describes the provided converters, in order of precedence (the first IMessageConverter that works is used):

ApplicationJsonMessageMarshallingConverter: Variation of theSteeltoe.Messaging.Converter.NewtonJsonMessageConverter. Supports conversion of the payload of theIMessageto/from POJO for cases whencontentTypeisapplication/json(DEFAULT).ObjectSupportingByteArrayMessageConverter: Supports conversion of the payload of theIMessagefrombyte[]tobyte[]for cases whencontentTypeisapplication/octet-stream. It is essentially a pass through.ObjectStringMessageConverter: Supports conversion of any type to astringwhencontentTypeistext/*. For objects, it invokesToString()method or if the payload isbyte[], it usesEncodingUtils.Utf8.GetString(..).

When no appropriate converter is found, the framework throws an exception. When that happens, you should check your code and configuration and ensure you did not miss anything (that is, ensure that you provided a contentType by using a binding or a header).

However, most likely, you found some uncommon case (such as a custom contentType perhaps) and the current stack of provided IMessageConverters

does not know how to convert. If that is the case, you can add custom IMessageConverter. See User-defined Message Converters.

User-defined Message Converters

Steeltoe Stream exposes a mechanism to define and register additional IMessageConverters.

To use it, implement Steeltoe.Messaging.Converter.IMessageConverter, and add it to the service container.

At startup time, it will be discovered and then appended to the default stack of IMessageConverters.

NOTE: It is important to understand that custom

IMessageConverterimplementations are added to the head of the default stack. Consequently, customIMessageConverterimplementations take precedence over the default ones, which lets you override as well as add to the default converters.

The following example shows how to create a message converter bean to support a new content type called application/bar:

Startup.cs

public void ConfigureServices(IServiceCollection services)

{

// ...

services.AddTransient<IMessageConverter, MyCustomMessageConverter>();

// ...

}

MyCustomMessageConverter.cs

public class MyCustomMessageConverter : AbstractMessageConverter

{

public override string ServiceName { get; set; } = "MyCustomMessageConverter";

public MyCustomMessageConverter()

: base(new MimeType("application", "bar")) { }

public override bool CanConvertFrom(IMessage message, Type targetClass)

{

return Supports(targetClass);

}

protected override bool Supports(Type clazz)

{

return clazz == typeof(Bar) || clazz == typeof(string);

}

protected override object ConvertFromInternal(IMessage message, Type targetClass, object conversionHint)

{

var serializedBar = Encoding.Default.GetString((byte[])message.Payload);

var serializationOptions = new JsonSerializerOptions { PropertyNameCaseInsensitive = true };

var bar = JsonSerializer.Deserialize<Bar>(serializedBar, serializationOptions);

return $"{bar.Name} has been processed";

}

}

Inter-Application Communication

Stream enables communication between applications. Inter-application communication is a complex issue spanning several concerns, as described in the following topics:

Connecting Multiple Application Instances

While Stream makes it easy for individual applications to connect to messaging systems, the typical scenario for Stream-based applications is the creation of microservices pipelines, where microservices send data to each other.

You can achieve this scenario by correlating the input and output destinations of "adjacent" applications.

Suppose a design calls for a Time Source application to send data to a Log Sink application. You could use a common destination named ticktock for bindings within both applications.

Time Source (that has the channel name output) would set the following setting:

"spring": {

"cloud": {

"stream": {

"bindings": {

"output": {

"destination": "ticktock"

}

}

}

}

}

Log Sink (that has the channel name input) would set the following property:

"spring": {

"cloud": {

"stream": {

"bindings": {

"input": {

"destination": "ticktock"

}

}

}

}

}

Instance Index and Instance Count

When scaling up Stream applications horizontally, each instance can receive information about how many other instances of the same component exist and what its own instance index is.

Stream does this through the configuration setting spring:cloud:stream:instanceCount and spring:cloud:stream:instanceIndex settings.

For example, if there are three instances of a "HDFS sink component", all three instances have spring:cloud:stream:instanceCount set to 3, and the individual instances have spring:cloud:stream:instanceIndex set to 0, 1, and 2, respectively.

When Steeltoe Stream components are deployed through Spring Cloud Data Flow, these settings are configured automatically; when you launch the Stream components independently, these settings must be set correctly.

By default, spring:cloud:stream:instanceCount is 1, and spring:cloud:stream:instanceIndex is 0.

In a scaled-up scenario, correct configuration of these two settings is important for proper partitioning behavior (see below), and the two settings are always required by certain binders in order to ensure that data are split correctly across multiple consumer instances.

Partitioning

Partitioning in Stream applications consists of two tasks:

Configuring Output Bindings for Partitioning

You can configure an output binding to send partitioned data by setting one and only one of its partitionKeyExpression or partitionKeyExtractorName properties, as well as its partitionCount property.

For example, the following is a valid and typical configuration:

"spring": {

"cloud": {

"stream": {

"bindings": {

"output": {

"destination": "partitioned.destination",

"producer": {

"partitioned": true,

"partitionKeyExpression": "Headers['partitionKey']",

"partitionCount": 5

}

}

}

}

}

}

Based on the above configuration, data is sent to the target partition by using the following logic.

A partition key's value is calculated for each message sent to a partitioned output channel based on the partitionKeyExpression.

The partitionKeyExpression is an expression that is evaluated against the outbound message for extracting the partitioning key.

If an expression is not sufficient for your needs, you can instead calculate the partition key value by providing an implementation of Steeltoe.Stream.Binder.IPartitionKeyExtractorStrategy and adding it to the service container.

If you have more then one IPartitionKeyExtractorStrategy configured, you can further filter it by specifying its name with the partitionKeyExtractorName setting, as shown in the following example:

spring:cloud:stream:bindings:output:producer:partitionKeyExtractorName=customPartitionKeyExtractor

spring:cloud:stream:bindings:output:producer:partitionCount=5

. . .

public class CustomPartitionKeyExtractorClass : IPartitionKeyExtractorStrategy

{

public string ServiceName { get; set; } = "customPartitionKeyExtractor";

.....

}

Once the message key is calculated, the partition selection process determines the target partition as a value between 0 and partitionCount - 1.

The default calculation, applicable in most scenarios, is based on the following formula: key.GetHashCode() % partitionCount.

This can be customized on the binding, either by setting an expression to be evaluated against the key (through the partitionSelectorExpression setting) or by configuring an implementation of IPartitionSelectorStrategy as a service and adding it to the service container.

Similar to the IPartitionKeyExtractorStrategy, you can further filter it by using the spring:cloud:stream:bindings:output:producer:partitionSelectorName setting when more than one service of this type is available in the container, as shown in the following example:

spring:cloud:stream:bindings:output:producer:partitionSelectorName=customPartitionSelector

. . .

public class CustomPartitionKeyExtractorClass : IPartitionSelectorStrategy

{

public string ServiceName { get; set; } = "customPartitionSelector";

.....

}

Configuring Input Bindings for Partitioning

An input binding (with the channel name input) is configured to receive partitioned data by configuring its partitioned setting, as well as the instanceIndex and instanceCount settings on the application itself, as shown in the following example:

spring:cloud:stream:bindings:input:consumer:partitioned=True

spring:cloud:stream:instanceIndex=3

spring:cloud:stream:instanceCount=5

The instanceCount setting represents the total number of application instances between which the data should be partitioned.

The instanceIndex setting must be a unique value across the multiple instances, with a value between 0 and instanceCount - 1.

The instance index helps each application instance to identify the unique partition(s) from which it receives data.

It is required by binders using technology that does not support partitioning natively.

For example, with RabbitMQ, there is a queue for each partition, with the queue name containing the instance index.

If autoRebalanceEnabled is set to False, the instanceCount and instanceIndex are used by the binder to determine which partition(s) the instance subscribes to (you must have at least as many partitions as there are instances).

The binder allocates the partitions.

This might be useful if you want messages for a particular partition to always go to the same instance.

When a binder configuration requires them, it is important to set both values correctly in order to ensure that all of the data is consumed and that the application instances receive mutually exclusive datasets.

While a scenario in which using multiple instances for partitioned data processing may be complex to set up in a standalone case, Spring Cloud Data flow can simplify the process significantly by populating both the input and output values correctly and by letting you rely on the runtime infrastructure to provide information about the instance index and instance count.